Canyon Pintado's Rock Art

Subscribe Now!The rock walls of Canyon Pintado have served as a massive canvas for thousands of years, preserving the history of the land and it's people against both natural and human destruction.

(This story originally appeared in the July/August 2014 CL issue of Colorado Life Magazine)

While the British colonies along the continent’s Eastern Seaboard were declaring their independence and rising up in revolution in 1776, Colorado was still Spanish territory, exactly 100 years from becoming a U.S. state. In that momentous year, Spanish priests Francisco Atanasio Domínguez and Silvestre Vélez de Escalante led an expedition in the desert southwest searching for a safe passage between Santa Fe, New Mexico, and California. When they arrived to the arid lands of the Colorado Plateau south of present-day Rangely, they were shocked to find strange scrawled and chiseled figures, some with threatening warlike stances, staring back at them stoically from the rocky canyon walls above.

“Halfway down this canyon toward the south, there is a very high cliff on which we saw crudely painted three shields and the blade of a lance. Farther down on the north side we saw another painting which crudely represented two men fighting .For this reason we called this valley Cañon Pintado,” Escalante wrote in his journal on Sept. 9, 1776, christening the region as the “Painted Canyon.”

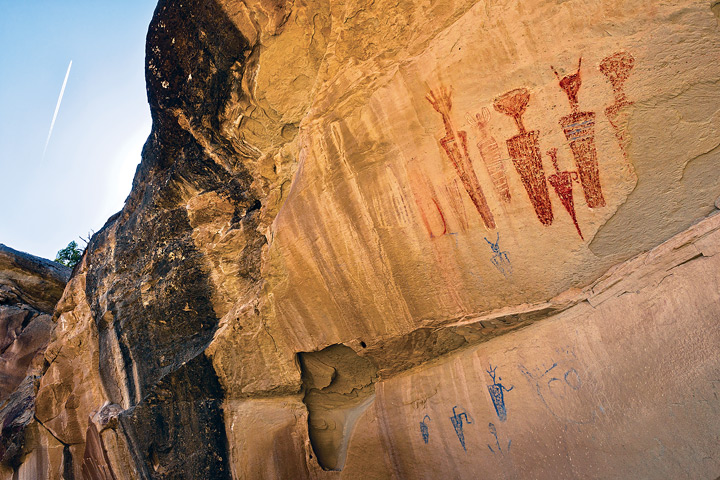

The mystery of who left this rock art and why has intrigued visitors to this region since the Dominguez-Escalante expedition. There are two types of images: petroglyphs, which are pecked or rubbed into rock with tools or by tapping with another stone, and pictographs, which are painted on rock using pigments from animals, plants or minerals. The rock walls around Rangely depict humans, some of which are rather oddly shaped; animals native to the area, such as lizards and bighorn sheep; and geometric or abstract shapes. Present-day people have come up with different theories about the rock art’s origin. The ancient images are variously described as waypoints for nomadic hunters, histories of significant events, records of spiritual experiences, doodles left by bored children or even evidence of ancient extraterrestrial visitors.

Canyon Pintado is believed to have been occupied by prehistoric people for as long as 11,000 years. In this land of converging cultures, most of the rock art that exists today is attributed to the Fremont Indians, who lived in the region from about A.D. 650 to 1200, when they seemingly disappeared. The Fremont probablydidn’t vanish but instead migrated south to escape drought conditions or political upheaval, much like their Ancestral Puebloan cousins of the Mesa Verde region, who abandoned their cliff dwellings around the same period.

Through the centuries, the style of Fremont art evolved, possibly reflecting profound changes in their society. Early art known as the Barrier Canyon style featured corn stalks and “CarrotMen,” anthropomorphic forms with floating triangular bodies wearing mystical headdresses, revealing a reverence for agriculture and ritual. One such site, called the “Sun Dagger,” appears to use the play of light and shadow at the corner of an overhanging ledge as a planting calendar to record celestial events like solstices and equinoxes.

Another site shows the mythical figure of Kokopelli. Legends of this humpbacked flute player are shared by many south western cultures, though theories of his origin and purpose range from a human fertility symbol to a roving minstrel, trader, holy man, hunter or trickster. In the myths of the Pueblo and Hopi peoples, Kokopelli carried seeds, babies and blankets in his hump,or a backpack of goodies, to give the maidens he seduced during corn-planting season. Later rock art subjects, like those witnessed by Escalante, became more detailed and violent – figures holding shields, spears and the human heads of possible sacrificial or battle victims – hinting at the strife that may have prompted the Fremont people to leave the area.

From the departure of the Fremont culture until the late 1800s, Ute Indians also left their mark on Canyon Pintado. Subjects like horses and firearms, neither of which were in Colorado when the Fremont people were, are telltale signs a rock art panel is of Ute origin. One of the most famous of these is the Crook’s Brand Site, where a Ute 7th Cavalry scout carved a horse into the rock with a brand that researchers traced to the brand used by General George Crook’s regiment during the Indian Wars of the 1870s. The artist perhaps returned clandestinely to carve the petroglyph after the Utes were forcibly removed from their lands following the killing of Indian agent Nathan Meeker 55 miles to the east during a Ute uprising at the close of the decade.

Rock art also has been left by lost or lonely ranchers in recent times. One such inscription believed to be left by a 19th-century cowboy reads: “We are here because we ain’t in hell, but we are on our way.” Another panel, signed by a sheepherder named Paco Chacon in 1975, depicts a buxom pin-up girl whose body has unfortunately been used for target practice by vandals.

Today, finding rock art sites in Canyon Pintado is less arduous than in the days of Dominguez and Escalante thanks tothe designation of the region as a national historic district and preservation efforts by the town of Rangely and the Bureau of Land Management. The friendly folks at the Rangely Museumare eager to assist visitors mapping their own explorations.Sixteen sites are marked on a self-guided road trip route snaking through U.S. Highway 64, Colorado Highway 139 (part of the Dinosaur Diamond Scenic Byway shared by Colorado and Utah) and Rio Blanco County Road 23. The museum occasionally offers guided tours on summer Saturdays. Dozens of other unmarked art sites and caves that perhaps were inhabited by ancient people also await adventurous travelers.

Though close-up access to exquisite examples of rock art is only limited by time, weather and the occasional need for a high-clearance vehicle, visitors are encouraged not to touch the art. It is so fragile that oil and perspiration from skin can be transferred to the pigments, causing them to be more susceptible to the elements and degrade faster. Damage to sites already has occurred where visitors added their own chalk outlines,attempted to cut art from rock panels or shot bullets at it. With the care of modern visitors, rock art that has persisted for a thousand years will still be waiting for the expeditions of generations to come.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

(This story originally appeared in the July/August 2014 CL issue of Colorado Life Magazine)

The information below is required for social login

Sign In

Create New Account