SOUTH OF GRAND Junction, Highway 141 runs southwest from Whitewater, crosses the Gunnison River and winds into a jagged canyon strewn thick with tumbled boulders. Lichens speckle sharp rocks like history’s map. It’s a severe canyon entrance, perhaps like entering purgatory, rather than exalted lands of coursing waters, towering cliffs and flowing grass.

The road climbs through the rocky mayhem and eases over Nine Mile Hill, opening into a pleasing narrow valley dotted with ramshackle ranches, dramatically hemmed in by sheer cliff walls jutting toward blue sky. Thus begins the Unaweep-Tabeguache Scenic and Historic Byway, a 150-mile ribbon of road in far western Colorado through a thinly populated area where the high Uncompahgre Plateau meets the red rock deserts of the Southwest.

It’s not like this part of the state was forgotten, but more that it has never been known, lying so close to Utah that it just falls off the Colorado map. However, the lives of people here tell the tales of all Colorado – romance and reality, dreamers and doers, ancients and newcomers, bust and boom – all lived out in the natural theater of the Unaweep and the wild canyons converging on the Dolores River Valley.

Precambrian rock is almost unfathomably old, but it still defines this land as the road runs between immense cliffs along a valley floor dotted with the ranches of working people, the yards littered with machinery, worn-out trucks, stock trailers, dogs.

In the evenings, wood smoke lifts from their chimneys, the valley floor chills in the cliff’s shadow until the planet rotates far enough for the sun to shine down upon the Unaweep again and warm the sage, cottonwoods, cows and quarter horses below. People drive home from work on the land, or from work in distant towns. Every one of them waves.

“Unaweep” means “parting of the waters” or “canyon with two mouths,” depending on who you ask. But long ago, the Utes realized the important point, that Unaweep Canyon is the only known canyon in the world with a divide that drains water out each end. West Creek flows out one end and East Creek out the other. It’s not a radical divide visually, and if you blink, you might even miss it.

West of the divide and rimmed by cottonwoods, shallow lakes stretch out along the valley, a wealth of water feeding thick grass that lures in huge elk herds from the Uncompahgre above. Hundreds of elk feed on the grassy fields near the base of Thimble Rock, a giant stone fin. Highway 141 eases around it and passes Driggs Mansion, an arched stone house of dreams collapsing back into rubble.

The dream behind the mansion belonged to Colonel Lawrence La Tourette Driggs who homesteaded 320 acres here. The mansion took masons four years to build, but the Driggs lived here only briefly. The story is that his wife, from the East, took one look at the remote area and quickly took the train home.

Stories like that of the Driggs are common, settlers learning the area didn’t suit them, selling their land and moving on. But those aren’t the stories that matter, not like those of families who pulled back on the reins and settled in for the long haul.

Janice and Oscar Massey name six generations of their family that have lived in the Unaweep, working ranches up and down the canyon and high cattle country on the Uncompahgre Plateau above. Three of their four sons ranch here, and despite the lure of modern influences, Janice and Oscar’s grandchildren are learning this lifestyle as well.

Oscar has lived in the Unaweep for 60 years, Janice all her life. Their ancestors settled early, coming as trappers before the Utes left, as Mormons skirting polygamy laws, as miners who became ranch owners. Today, the Masseys run cattle from Palisade all the way to Gateway, a 60-mile swath across the high country.

Sitting in their house, a short stone’s throw from Highway 141, one gets the feeling that Oscar and Janice could tell stories about this area for days, once you get them started – tales not only of ranching, but how uranium shaped people, who built the schools, who married whom, the best seat when eating at a long table of miners, and of course, the legends of settler survival passed down through generations.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

“Once, my grandfather was riding a skittish horse,” remembers Oscar, “and he bent down to open a gate or something. That horse threw him and broke his femur, or his hip. I don’t know. He tied himself on his horse and rode from here all the way to Moab.” People were tougher back then, he said. Life was tougher.

Maybe people accepted more risk, or just trusted more. “My dad, he used to put my sisters on a pack mule, one on each side, and just send them up the mountain to the high pasture,” Oscar said. “It was 15 miles but the mules knew their way and just took them.”

One of their sons walked in, Austin, a friendly man dressed in denim, a red moustache under a big weathered hat. Talking about what it was like to grow up in the Unaweep, Austin recalled, “We got up at 4:30 to make it to school. We were too far from town to do any sports, but we spent hours climbing the cliff walls around here.”

Oscar pointed out a slanted line up the nearby cliff and said, “The boys climbed that. You wouldn’t catch me dead up there.” Then, looking at the living room wall covered by photos of their grandkids, he pointed out a young woman and said, “That’s Danielle, Austin’s daughter. She can train a horse to talk and walk. She’s just a natural.” For many in the Unaweep, these are things that matter, skill with horses, courage, the land, family and longevity.

Just down from the Masseys, the road passes Campbell Point, site of an unusual murder in the valley in 1885. John L. Campbell apparently shot his business partner, Sam Jones, then carried the body on horseback to the top of the cliff where he threw if off. A search party later found the body by following circling buzzards. Oddly enough, the point carries the name of the murderer and not the deceased.

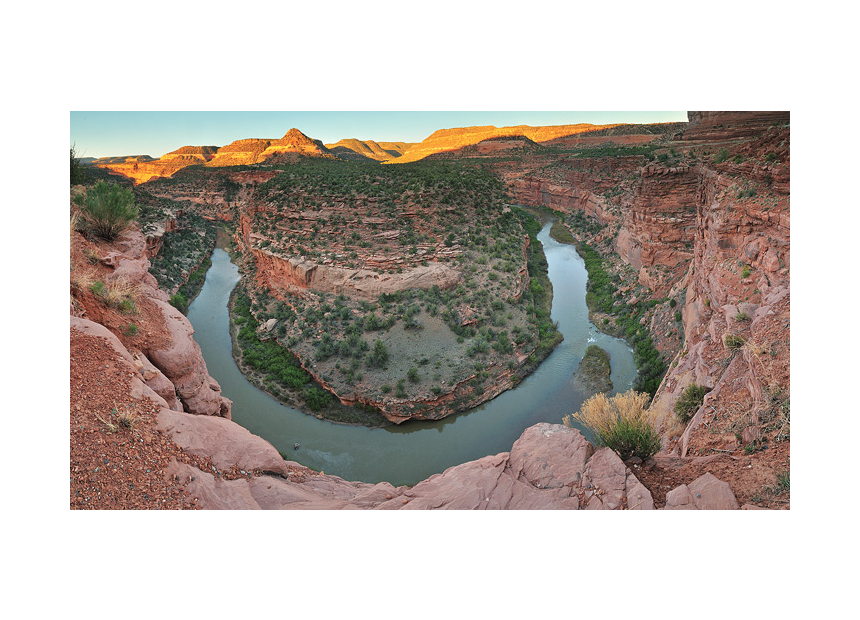

AS THE ROAD continues southwest and drops down the divide, Unaweep Canyon officially ends in the Dolores River Valley. Four major canyons converge here, like giant red spokes radiating outward from the worn town of Gateway. The town has waxed and waned over the last century, but besides a few houses, a post office, a school and a diner that’s rarely open, there is still little to Gateway beyond a wealth of stunning scenery including the Palisade, a towering red rock mesa that looms nearly 2,000 feet over town.

Drive through the faded town, cross the Dolores River and turn south and suddenly it appears like a mirage, the Gateway Canyons Resort, an upscale destination resort and conference center owned by John Hendricks, founder of the Discovery Channel television networks. After the simplicity of the working ranches and barbed wire fences, the contrast is striking.

People have been buying and selling ranches in this valley since the first acre was fenced, so the purchase of several thousand acres in the area was nothing new. Hendricks learned about Gateway from an ad he read in the New York Times that simply said, “Ranch for sale in the spectacular red rock canyon country southwest of Grand Junction, Colorado.” He flew out, purchased the ranch and starting buying more land in an effort to preserve Gateway’s open western feel.

It must have seemed like fate. Hendricks had harbored dreams of the American West most of his life, enthralled by his father’s tales about traveling in the area in the 1920s and ’30s. The wild country around Gateway seemed to match his dreams perfectly.

Undoubtedly his vision and resources shocked some locals, as it does throughout Colorado when someone with more than you moves in next door. But it can’t be disputed that the Gateway Canyons Resort has breathed new life into Gateway by providing jobs, raising property values, purchasing computers for the school and grass for the soccer fields. Over the last few years, Hendricks has placed a good portion of his land in conservation easements in partnership with The Nature Conservancy and Mesa Land Trust, ensuring that these big tracts of land will stay whole forever.

From a few hundred feet above the valley floor in the resort’s helicopter, it’s easy to see how the land around Gateway inspires so many. Unaweep Canyon stretches out to the north, the white Precambrian cliff walls contrasting with the deep red Wingate sandstone above the Dolores River. To the east, the Uncompahgre Plateau rises up in forests of aspen and pine. To the west, the snowcapped La Sal Mountains of Utah beckon, looking close enough to touch. This is the incredible natural backdrop where the Massey family has made their life, and where Hendricks realized his childhood dreams.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

From Gateway, Highway 141 follows the Dolores River upstream through a dramatic red-walled canyon, stunning and wild. People don’t live along this stretch and the few gravel roads that branch out from the highway enter untamed lands. Follow one of these roads west as it winds slowly upward through shattered stone and a maze of cliffs into one of Colorado’s least-disturbed piñon-juniper mesa lands. This is the Sewemup Wilderness Study Area, an area that encompasses the Sinbad Valley and areas virtually untouched by humans.

This remote area attracted a certain type of person, mostly outlaws. The McCarty Gang spent time here, allegedly mixing with Butch Cassidy and company, who were hiding out just a few miles west. After most of the McCarty Gang were shot dead during a bank robbery in Delta, the lone survivor fled, but the Sewemup continued to attract men who needed a hideout far from the law.

A gang of cattle rustlers gave the area its name. They stole cattle from ranches along the Dolores and San Miguel Rivers, running them into hidden box canyons where they cut the old brand out and sewed up the skin. Once the skin healed, the Sewemup Gang re-branded and sold the cattle. To avoid detection, they built wooden steps over the slickrock. Once the gang left the area, ranchers tore down the trails and burned the log steps, once again making it extremely difficult to get into areas the outlaws once used.

Back on the main highway, the contrast between parched land and the flowing river feels striking, but completely natural. At some spots, water seeps straight from stone like magic, creating desert microclimates where fragile, soft plants cling to the rock. The air remains humid and cool in the cliff shadow. Lush growth stretches out from the seep like grasping arms trying to overcome the desert.

Few people travel this majestic road, and the canyon walls funnel the sound from approaching vehicles far away, but most of the time they simply echo the music from the ripples of the Dolores.

We humans often can’t seem to comprehend the intense complexity of the natural world, gravitating to things we can quickly grasp, human works. In the Dolores River Canyon it’s no different. Under the massive towering cliffs and mesas, most travelers stop at an overlook for the Hanging Flume, a nearly 10-mile-long waterway built to enable hydraulic placer mining at a claim a few miles down from the confluence of the Dolores and San Miguel.

What makes this particular flume unique is that it’s more than just a ditch in the dirt. Engineers and workers hung long sections of the flume straight from the vertical cliff walls high above the river – a ditch in the sky. It took three years to build the flume, 1889-1891, but was used for just three years until the “Panic of ‘93,” when the stock market plummeted along with mineral prices and they abandoned everything.

The southern end of the Unaweep-Tabeguache Scenic and Historic Byway climbs out of the canyonlands, but continues to traverse land and livelihoods dictated by minerals in the ground, including uranium and vanadium in the aptly named, but longgone town of Uravan.

In 1936, the U.S. Vanadium Corp. created Uravan, a mill town to dig out vanadium, used to make steel harder. Just a few years later, in the early 1940s, the government reclaimed the mine tailings and processed them to collect uranium. Some of this uranium was used in the Manhattan Project’s top secret atomic bombs that ended World War II. One local commented, “If we didn’t do that, I reckon we’d all be speakin’ Japanese.”

After Uravan, the road continues along the San Miguel River, then down Highway 145 through Nature Conservancy preserves and the simple town of Naturita before climbing to a high plateau near Norwood, where the horizons leap back in every direction. After the tight canyons, the land here feels immense and alpine, the summits of Lone Cone and the San Juans beckoning with snowy promises.

Although the designated byway soon ends, at least on the map, this beautiful route continues on to Telluride, Ridgway or full circle back to Whitewater. It’s a sparsely populated journey of canyons and mountains, cowboys and developers, the atomic industry and nature conservation, outlaws and dreamers. It encapsulates the essential history and reality of Colorado along a single ribbon of highway.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

The information below is required for social login

Sign In

Create New Account