THE LITTLE ITALIAN RESTAURANT on northwest Denver’s Tejon Street has a big reputation, and not just for authentic food. From the time Gaetano’s opened in Denver’s Little Italy neighborhood in 1947, everyone knew it as the mob’s hangout. The restaurant’s owners, the Smaldone family, simply called it “the place.”

In the 1950s and ’60s, the Smaldone name was notorious in Denver, instantly recognized as the strong arm of the mob. Banner headlines across the The Denver Post read “Smaldone Brothers Get 60-year Terms” and “Verdict Spells End for Smaldone Gang.”

Gaetano’s was the crime family’s headquarters, and the people hanging around the wood-paneled restaurant were a who’s who of the Colorado underworld.

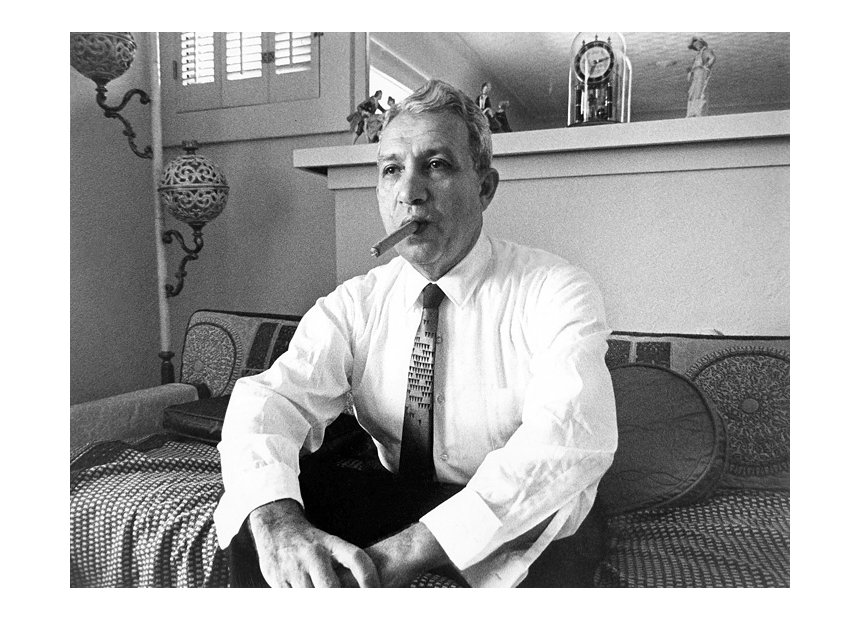

You could find family patriarch Clyde Smaldone – “Gaetano” is the Italian equivalent of “Clyde” – seated at the bar, always at his spot furthest from the door. Clyde looked every bit the part of an Italian-American mob boss, of average height and above-average weight, dressed immaculately in expensive suits and the look punctuated by an ever-present cigar.

Besides his intellect, Clyde was known for his talent for making friends, whether it was with his neighbors, Mafia kings like Al Capone and Carlos Marcello, or Colorado Gov. Ralph Carr. Colleagues and arresting officers alike described Clyde as a gentleman.

Clyde and his younger brother Eugene, who went by Checkers, often would visit with the patrons at Gaetano’s, inquiring about the food that was in the early days prepared by their mother in the restaurant’s kitchen.

Like a good-cop, bad-cop routine, Checkers was the Smaldone with the tough-guy reputation. He had the closest ties to the feared Mafia bosses to the south in Pueblo. But Checkers wasn’t all intimidation; with a few drinks under his belt, those at the bar would hear him launch into an impromptu one-man opera performance.

In later years, Clyde and Checkers were less involved in the family’s rackets, and youngest brother Clarence, known as Chauncey, took over. Chauncey, the handsomest of the brothers, had a favorite spot at Gaetano’s at a table in the far back (Table 404 to the servers who work there today), where you’d see him eating his now-famous “Chauncey Burger” – a half-pound of ground chuck, melted mozzarella and roasted Italian peppers, served with a side of the house red sauce. The Chauncey Burger is still on the menu.

From Gaetano’s, the Smaldones ruled north Denver from the 1930s through the 1970s. But you won’t find them there anymore; the three brothers passed away over the last two decades, and the family sold Gaetano’s six years ago. Still, the place is saturated with their memory. The dining room looks the same as the last time the Smaldones remodeled in 1973, and you can sit at Clyde’s favorite barstool.

Most of the patrons are local, and many of them knew the Smaldones, says Gaetano’s general manager, Don Knowles.

“Ten out of 11 of them have nothing but great things to say about the family,” he said. People tell him that no one in the neighborhood ever went hungry, no matter how bad the times were – the Smaldones would always help out.

THAT’S THE TRICKY THING about figuring out the Smaldones. Depending on who you talk to, they were either modern-day Robin Hoods or shoot-’em-up Mafiosi straight out of a gangster flick. In reality, they were neither.

There’s no doubt that the stories about their generosity are true. Even in their heyday, when The Denver Post waged a media campaign against organized crime, the newspaper’s Roundup Magazine gave Clyde and Checkers credit for helping destitute north Denver families with milk and groceries, secretly paying college tuition for local boys, and funding Catholic orphanages.

“Each Christmas they donate quantities of athletic equipment to the homeless waifs and ‘feed ’em good’ at Gaetano’s,” the magazine wrote.

There also was a darker side to the Smaldones. No matter how you spin it, they made their money by breaking the law – first bootlegging, then running gambling rackets and loansharking. Some of the people associated with them died violently.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

CLYDE AND CHECKERS, born in 1906 and 1910, respectively, were the oldest sons of the nine children of Raffaele and Mamie Smaldone, immigrants from Potenza, Italy. It was in Denver’s north-side Italian enclave during Prohibition that they started building their empire. As teenagers, they would find where the bootleggers stashed their illicit booze. Then they stole it and sold it to speakeasies.

They graduated into making their own liquor, then started trucking in premium whiskey from Canada, and finally, buying it from Al Capone’s Chicago outfit.

Colorado’s rival gangs fought for control of bootlegging, and during prohibition there were some 30 gangland murders. In the south, the Dannas out of Trinidad and the Carlinos from Pueblo fought for supremacy.

In Denver, the Smaldones' employer was Joe Roma, the 5-foot-1 mob boss kingpin known as “Little Caesar.” And like his namesake, Roma met a bloody end when in 1933 he was shot seven times – six in the head – in his North Denver home. The killers were never prosecuted, and the Smaldones always denied involvement, but Roma’s death meant that the Smaldones were undisputed kings of the Italian mob in Denver.

Clyde and Checkers spent the last days of Prohibition in Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary, returning to Denver in 1934 after 18 month stints to find their bootlegging business obsolete. They moved seamlessly to gambling, where they worked with Ova Elijah “Smiling Charlie” Stephens, who ran a high-end restaurant that doubled as a casino. Stephens, Clyde and Checkers were convicted in the car-bombing of Stephens’ erstwhile casino partner and were sent to state prison at Cañon City.

After the Smaldones were freed in the early 1940s, they found their greatest success through their mother’s cooking. In 1947, the brothers founded Gaetano’s, which thrived.

That same year they opened a casino, dubbed Monte Carlo, in the old mining town of Central City. Respectable people from Denver and across the state flocked to play craps, roulette and slot machines. Clyde’s charm persuaded city officials to look the other way, and as a token of thanks, the Smaldones paid for new waterlines for Central City, restored dilapidated houses and funded a school lunch program.

“If you know how to talk to people you can make money anywhere and you don’t have to say, ‘It’s a bribe,’” Clyde said years later.

The Smaldones’ casino in Central City was illegal at the time, but Clyde predicted such gambling would be legalized if the government knew how much money there was to be made. But it took more than 40 years before the state approved gambling in Central City and other mountain towns, where many casinos now do booming – and legal – multimillion dollar business.

The Smaldone gambling racket spread across Colorado in the late 1940s and included at one time more than 500 slot machines. They also did a lot of business taking bets on sporting events.

The Smaldones’ success rankled prosecutors, who made an allout push to get them. Checkers was charged with tax evasion and was to stand trial. When the Smaldones sought out potential jurors to coax a “not guilty” verdict, they were accused of jury tampering. They were tried and convicted, but the judge’s ruling was thrown out. Instead of going through a second trial with a new judge, Clyde and Checkers worked out a plea bargain in which they would each serve three concurrent four-year terms. But the judge changed the agreement to three consecutive terms, and the brothers were sentenced in 1953 to 12-years in Leavenworth.

The family business continued with the youngest Smaldone brother Chauncey, taking control, along with nephew Paul “Fat Paulie” Villano. Clyde retired from his role when he got out in 1963, but Checkers stayed involved. In the 1970s, the family struggled with independent bookmakers who no longer recognized the Smaldone control of gambling in Denver. One such upstart, former University of Colorado football player Skip LaGuardia, was killed by a shotgun blast to the face outside his Denver home. The Smaldones were widely thought to be behind it, but no charges were made.

The Smaldones’ power continued to fade as the main players grew old and no one was recruited to take their place. By the time Checkers was sentenced to another prison term in the 1980s for loansharking, the Smaldones had effectively ceased to exist as a criminal enterprise in Denver.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

THE MOST NOTICEABLE change at Gaetano’s since the days when the Smaldones held court is the tongue-in-cheek slogan adopted by the new ownership: “Gaetano’s – Italian to die for.”

Gene Smaldone notices it when he slides into a booth for lunch and for a magazine story interview. The booth seat is black, and there’s a white cloth on the table. Gene orders the rigatoni with red sauce.

Gene is the elder of the two sons of Clyde and his wife, Mildred. Gene is trim and looks two decades younger than his 81 years, and in his khakis and green windbreaker, he comes across nothing like his suit-wearing father. He never got into his family business, never even smoked or drank. He was a North High and University of Denver football star who followed that path into coaching before entering a long and lucrative career in real estate. Gene shrugs off the mention of his family as mobsters.

“That was just my dad,” he says. “These other guys were my uncles and friends. I thought we were just like any regular family.”

But the legacy follows him, and he’s come to embrace it, focusing on the good things his family did. He helped arrange the interviews that provided the raw material for a 2009 book, Smaldone: The Untold Story of an American Crime Family, written by friend and retired Denver Post columnist Dick Kreck, who joined us at the table.

“You won’t find anybody in north Denver who has anything bad to say about them, because they gave money to the orphanages and the church and people on the street,” Kreck said.

The Smaldone name still means something to people here, Gene said. He talks about his wife’s recent grocery shopping expedition, how when it was time to pay, the woman at the checkout stand noticed the name on the credit card.

“She says, ‘Oh, are you related to the Smaldones?” the clerk said. “And Linda says ‘yes.’ And so the clerk says, ‘Can I carry your groceries out for you?”

But being a Smaldone can be something of a burden, too, and name recognition hasn’t always been so kindly expressed. We talked a few days later with Gene’s younger brother Chuck, who recalled his first day of first grade.

“I can remember they were calling the roll and there was a dead silence” after his name was called. “The teacher asked if I was part of the gangsters, or something like that, in front of the whole class,” Chuck said. “I was mortified.”

His parents, especially his mother, were adamant that Gene and Chuck not follow in their father’s line of business. Clyde had chosen his path almost out of necessity, to support his parents and younger siblings, and he never finished high school, he made sure his sons went to the best schools and got college degrees.

“My mother told my brother and I that because of our name, we had to be twice as good as everybody else, because people expected us to be bad,” Chuck said. Like his brother, Chuck defied expectations, making a lawful living as co-owner of Duane's Clothing menswear shop in Arvada.

When weighing the Smaldones’ crimes against the good things they did for people, the fact that they steered their children away from the family business – and in so doing guaranteed the end the criminal empire they built – is perhaps another weight on the “good” side of the scale.

But the Smaldone name still has the power to sparks imaginations. After the book on the family came out, Gene and Chuck started fielding calls from people interested in telling the Smaldones’ story in a movie; they recently met with an established screenwriter to work on a treatment. If their family appears on the big screen, the brothers want it to break from mob clichés and show the way the Smaldones helped others.

Hollywood depictions of mobsters are sometimes ridiculous, Chuck says, singling out The Sopranos as making them look “dumb.” The level of violence is always amplified in the movies, but some films hit closer to home. The wedding scene that opens The Godfather was reminiscent of Gene’s wedding in 1951, where 500 guests were invited, and 1,500 showed up.

And so the Smaldone legacy lives on, somewhere between myth and reality, between good and bad, and possibly, on the big screen, where immortals are made.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

The information below is required for social login

Sign In

Create New Account