The Mystery of Alfred Packer

Subscribe Now!It's was no secret that prospector and blizzard survivor Alfred Packer once dined on human flesh, but was he driven to cannibalism by desperation, or was the preparation of his unusual meal premeditated?

(This story originally appeared in the March/April 2013 CL issue of Colorado Life Magazine)

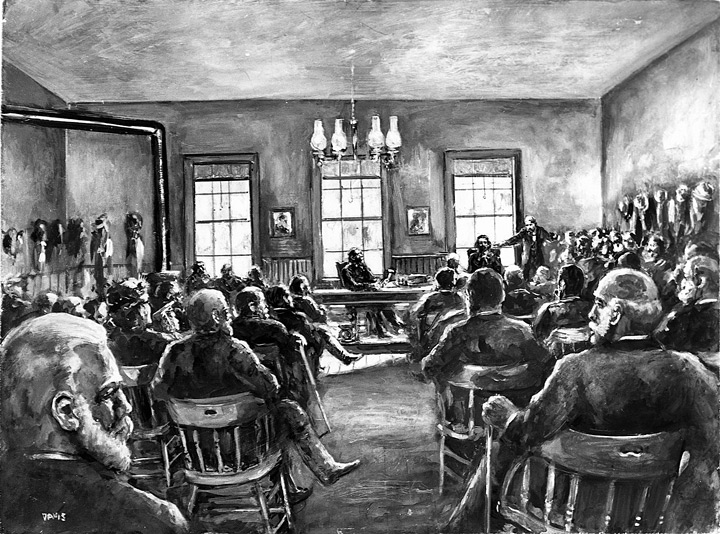

Government official Charles Adams summoned Alfred G. Packer to his office on the Los Pinos Indian agency, determined to find out what really happened to Packer’s five traveling companions.

“I believe these men are dead and you know something about it,” Adams said. “You might as well tell the truth. If the matter is as I suspect, you are more to be pitied than blamed.”

Several minutes passed. Packer said nothing.

Three months earlier, in February 1874, the lanky, blue-eyed 31-year-old was one of six gold prospectors to venture into southwest Colorado’s San Juan Mountains during one of the worst winters in memory. They were headed for the Indian agency south of present-day Gunnison, but Packer was the only one who arrived. Though he claimed the rest of his party left him behind after his feet got too frozen to keep up, rumors soon spread that he had murdered his comrades for their money.

Perhaps feeling cornered by Adams’ interrogation, Packer finally broke his silence with a cryptic, disturbing observation: “It would not be the first time that people had been obliged to eat each other when they were hungry.”

And so, through tears, Packer began to confess. It was to be the first of many confessions. He would recount his story a number of times over the next three decades, with the details changing in each telling. To this day, no one knows if Packer was the blameless victim of blizzards and starvation, or a calculating murderer who led five men to their doom. But there is one detail that was the same in each confession: He survived more than a month in the frozen wilderness by eating human flesh. Alfred G. Packer was a cannibal.

Into the blizzard

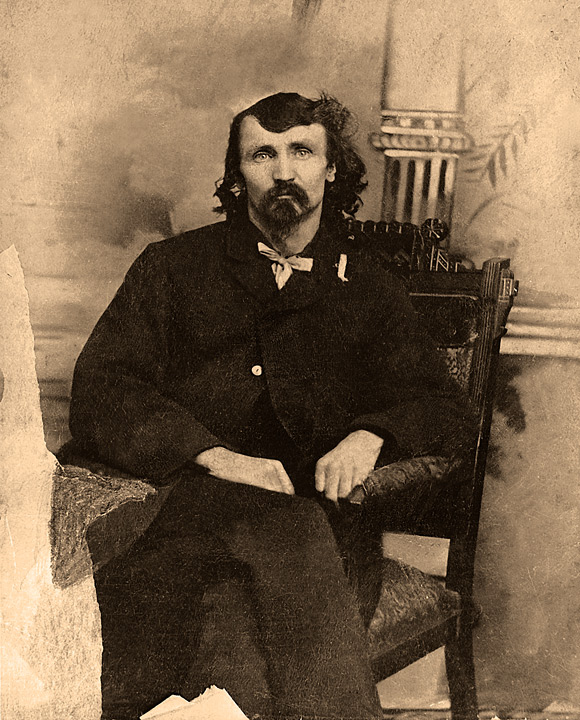

Packer was born near Pittsburgh on Nov. 21, 1842, though he claimed his birthday was Jan. 21. This ambiguity is hallmark of Packer’s life. There are two stories for even the most basic details, including his name. The spelling was Alfred in all official documents and contemporary newspapers, but he repeatedly signed his name “Alferd.” He left his parents, brother and two sisters at a young age, and by his late teens, he was living as a shoemaker in Minnesota.

All his life, Packer suffered from epilepsy, a disorder then thought to be linked to insanity. He enlisted with two different Union regiments during the Civil War, but he served with each for less than a year before getting discharged due to seizures, which occurred every two days, if not more frequently.

He spent the decade after the war drifting from job to job – hunter, hard-rock miner, trapper, teamster, guide – but despite his various explanations for his seizures, his employment invariably ended when his ailment manifested itself. By 1872, Packer arrived in Colorado. He worked as a miner in Georgetown, where he lost part of his left pinky and index finger to an errant sledgehammer blow. He wandered to Utah in 1873, making a poor living at the mines there. Then came word of a new gold strike in Colorado, and a group of would-be gold hunters – strangers to one another – gathered in Bingham Canyon, Utah, eager to get first crack at the untapped riches of the San Juans. Among them was Packer, who touted his experience traveling the mountains of Colorado.

Another man on the trip, Preston Nutter, summed up the general opinion of Packer: “He was sulky, obstinate and quarrelsome. He was a petty thief willing to take things that did not belong to him, whether of any value or not.” Whether Packer actually did anything to warrant this assessment is unknown, but the stigma of his epilepsy might have contributed to the mistrust. He suffered “fits” while still in Utah. Once, while sitting by the campfire, he was overcome by a seizure and fell into the flames, overturning a coffeepot, which spattered its scalding contents on his face.

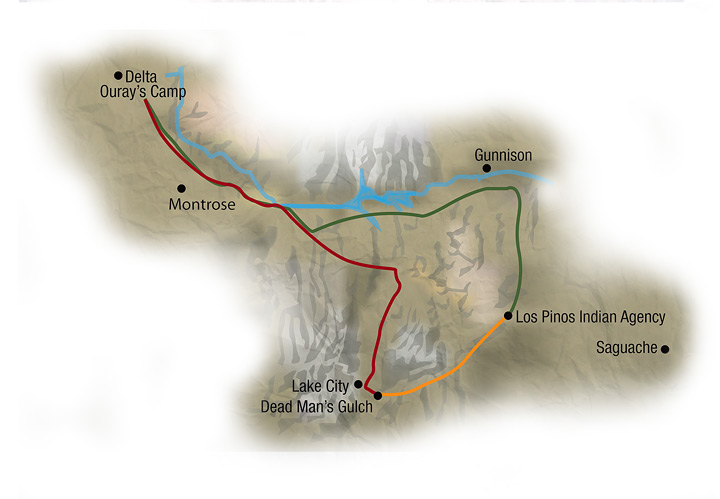

The party, which grew to include 21 men, set out in late autumn on a long journey by foot to the Colorado border. The travel was slow, game was scarce and early snow was heavy. Facing dwindling rations, the crew was forced to eat livestock feed. By late January 1874, the bedraggled lot made it to the Ute Indian camp of Chief Ouray in Colorado, near present-day Delta. Ouray shared his food and fire with the white men. He knew the country as well as anyone, and he warned his guests that to venture into the mountains at this time of year was to risk certain death – no Ute would attempt such a passage until spring.

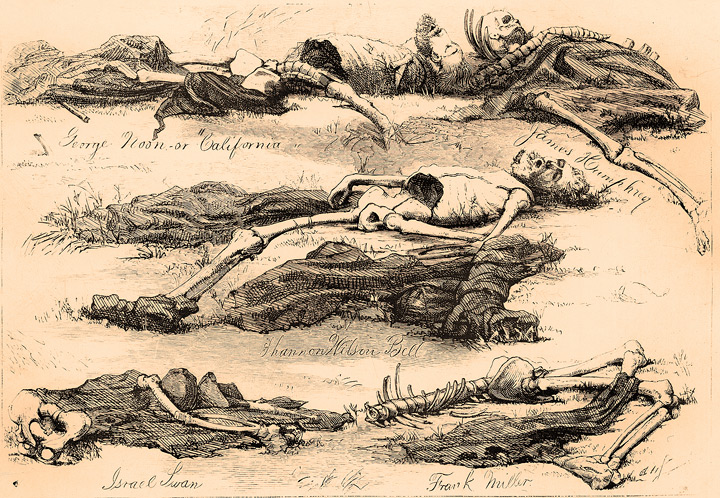

But some of the party of 21 refused to wait for better weather. Seeing there was no stopping them, Ouray gave directions: Travel east for seven days to the government cattle camp near Gunnison, then follow the creek south to the Los Pinos Indian Agency, from which it would be a relatively easy 40-mile trek to Saguache. Packer was the nominal guide for the group of six that departed Feb. 9. With him were George Noon, a teenager; Israel Swan, older than 60 and rumored to be carrying thousands in cash; James Humphrey; Frank Miller, a butcher from Germany; and stout, red-faced, red-haired Shannon Wilson Bell.

Subscribe to Colorado Life Magazine and receive thoughtful stories and beautiful photography featuring travel, history, food, nature and communities of Colorado.

The information below is required for social login

Sign In

Create New Account